|

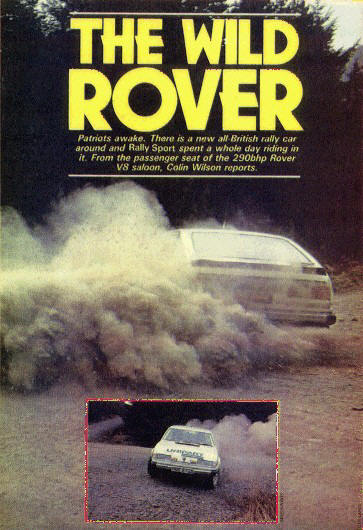

THE SPECTATORS PROBABLY get the best deal: they actually see the beast.

More important still, they get to hear the beast. For it is the sound of

it that forces its way into the mind there is absolutely no mistaking the

Rover 3500. No matter how dense the forest, it can be heard miles away,

bellowing like a McLaren CanAm car of old, or a refugee from Dukes of

Hazzard. With its Buick-derived V8 engine perhaps the noise should come as

no surprise, but such a deep-throated growl seems totally alien in an

environment accustomed to the sharp tones of a 16-valve straight four, or

even a high-revving V6 such as is found in the Stratos. The TR8 never

sounded this loud nor this healthy. The tight confines of the two seater's

underbonnet area did not permit the free-flowing exhaust system which has

been fitted to the saloon (and which, almost incidentally, accounts for

several extra horsepower). Lest all this preoccupation with noise seems

out of place, you should know that there exists for the Rover a 'quiet'

exhaust system, one which hardly reduces the power output at all. This

heavily silenced system will, moreover, almost certainly be used on the

long-distance marathon rallies for which the Rover was conceived. But BL

Motorsport's Rodney Lyne, whose project the Rover 3500 is, has always

appreciated the crowd pulling potential of raw noise. So he fitted the

simple, tuned-length open exhaust which produces such a glorious sound.

And as he said, "it would have been a shame to strangle it, wouldn't it?"

An early

indication of the Rover's appeal came at Esgair Dafydd, when Tony Pond

drove it into a far corner of the TV Rally Sprint paddock area. Within

seconds a highly unusual sight was to be seen: Hannu Mikkola's Audi

Quattro sat quite alone. The ever fickle spectators had abandoned it to go

and view the Rover - as had most of the Audi team, including Mikkola

himself... The appearance of the Rover as a course car on the Newtown

Stages (round three of the 1982 Century Oils/Rally Sport Championship)

came about as the result of a conversation between BL Motorsport Director

John Davenport and myself. This conversation centred on a passing thought

that ' maybe, just maybe, the Rover 3500 would make a suitable basis for a

club rally car, for use on events in Britain quite different from the

Peking-Paris slog for which the prototype has been built. For BL, an added

attraction was the fact that the Rover had never run on unseen stages and

apart from its all too brief three minutes or so of competition on the

Rally Sprint, had never been driven in real anger.

Colin Malkin

had done the bulk of the early development driving and was the obvious

choice to handle the car on the Newtown, despite the fact that he has

retired from competitive rallying ("I'm not quick enough for all this

forest racing I haven't even got a competition licence these days,

although I shall be there for the Peking-Paris"). The Rover itself was

very obviously a testing hack, lacking the detail niceties associated with

an actual competition car the passenger seat was large, comfortable and

very high-mounted ("these engineering types insist on seeing where they're

going", according to Lyne); the jack was mounted under the spare wheel,

which really slows down a change (as I would discover). What was clear,

however, was that this was a large car. Very large indeed. Even sitting

bolt upright in that huge armchair, the screen was a million miles away

and the window winders were beyond the reach of anyone wearing the seat

belts. And how many rally cars do you know with enough room on the

dashboard to sit a crash helmet with space to spare'? All this paled into

total insignificance the moment the key was turned. We were running at 00,

five minutes ahead of the field, and the whole population of Newtown

seemed to descend on the start line once that engine was running.

On

the road, it became clear that this beast also went. With a 5.3:1 diff

ratio it accelerates from 0 to 60mph in five seconds and reaches 100mph in

11.4s. Top speed is a mere 132mph! With the 4.5:1s diff which they intend

fitting for the marathon, by the way, top whack goes all the way to

150mph. Thank God we only had the 5.3... The noise level made

communication within the car impossible without inter-coms, which we

didn't have, forcing me to resurrect the system of hand signals which I

had last used back in the early 1970s when co-driving Peter Bryant in an

Imp. Luckily, Mr Malkin spent most of his early driving career in Imps

too, so he had no difficulty grasping the notion! The first stage - 11

miles in Hafren - confirmed at least one impression gained from watching

the TV Rally Sprint: this beast does not understeer by any stretch of the

imagination. No siree, if you like your rallying sideways, this is the car

for you. Also, it does not suffer from a lack of horsepower. With 290bhp

and an all-up weight much less than a TR8, the chief rule appears to be:

if in doubt, apply pedal A. You change up into fifth gear when pulling

around 125mph. Rather unnecessarily, I thought, Malkin explained that he

did not anticipate making a great deal of use of fifth gear. "We'll call a

full board meeting and get a unanimous decision by everyone present before

taking fifth," as he put it.

We agreed

that under the circumstances - the only Rover 3500 rally car in the world,

a driver employed because he's supposeded to be safe, a national magazine

editor in the passenger seat, and running as a course car on a relatively

minor rally - we would both look like a right pair of charlies if we bent

the thing... Despite the fact that those 11 miles were the first blind

miles ever tackled by the car (and the first for a great many years by

Malkin), we were 18 seconds faster than anyone entered in the rally. What

we failed to do at the end of the stage, however, was to step out of the

car and glance at our rear tyres. Instead, we set off into a second

11-mile stage using the rest of Hafren Forest. With six miles still to go,

a loud thumping noise from the rear announced the demise of one Michelin

TRX. Under the circumstances (see previous paragraph), we decided to pull

over and change the wheel, upon which we discovered that the tyre had not

actually punctured, just thrown off all its tread in protest. Having made

the change (which took forever, what with five wheel studs, the

aforementioned concealed jack and wheelbrace, and what must have been the

world's finest thread on the bolt which retained the spare wheel) we were

faced with the problem of reaching the end of the stage without

interfering with the event proper. Three cars having passed while we were

stationary we pulled out immediately behind the next and endured a

hairraising six miles in his dust, having to actually stop dead on several

occasions just to see which way the track went. A service area allowed us

to change the tyres, Malkin selecting one of Michelin's narrower and more

knobbly offerings, with considerably more depth of tread than the rather

softcompound TRXs which we had been using.

The seven miles of

Dyfnant felt much safer, although they may not have been any faster, as

the margin between ourselves and the actual rally drivers fell to nine

seconds. Another service area followed and this time we had learnt our

lesson: we faced another 11-mile stage, followed by an immediate 13 miler,

both in Hafren and with no easy way out between stages. We loaded two

spare wheels and planned to change the rears after the 11-miler. It nearly

worked. On that last, longest stage, Malkin really began to take control

of the Rover and we flew. Sometimes we even flew places we were not meant

to fly. Number one seed Trevor Prew reported that our tyre marks at one

point left the track on the left and rejoined the track many yards on from

the right. This was probably accurate. Malkin changed up to fifth

somewhere around there and I probably had my eyes shut. Certainly, I have

never travelled at that velocity in a forest before.

After the

rally, we discovered that the oversteer was not caused entirely by the

combination of high power and soft tyres - the whole rear suspension

system, which is mounted from a massive new bulkhead behind the front

seats, was coming adrift. The cracks in the bulkhead were less than 0.5 mm

wide, but with suspension arms 32in long, that translates into plenty of

movement at the working end. That was just one of the valuable lessons

learned by BL Motorsport. There were many others. The handbrake failed to

release when the lever was dropped, for example (it required a dab on the

footbrake to free it); with its long wheelbase, the Rover is inherently so

stable that tight hairpins demanded use of the handbrake to persuade the

rear end to break away. The only other way of achieving this was to boot

the throttle, but not even Leyland could afford the resulting tyre bill

for a whole season.

The car works. Or at least it will work when

the lessons learned on the Newtown have been put into play. The

combination of long wheelbase, wide track and long travel suspension eats

bumps and ruts that would throw lesser machines onto their roofs. The

steering is excellent, no doubt a legacy of the successful racing

programme, and the car turns into corners with no trouble at all. On fast

stages, it could be almost unbeatable. When everything is going well, it

doesn't even feel like a big car at all, although when matters start to

get out of hand, the length of the car does start to make itself felt. If

you can afford to use the 290bhp motor we had, most problems can be

resolved with the right foot. The sheer bulk (rather than weight) of the

car makes one feel that even if it did go off - the trees wouldn't stand a

chance. Reconsidering my opening paragraph, it is the crew who have the

best deal of all: they get to sit in the Rover, and that, is Fun. It

should also prove victorious, but that remains to be seen. BL Motorsport

are building "some more" of them, so we hope to find out later this year.

We now know what Rover did with the SD1, producing the 2nd most

competitive car (after the mini) ever from a British manufacturer.

The SD1 in competition today

A ROVER 3500

saloon as a club rally car? Ridiculous? Not necessarily. The basic model

was introduced in June 1976 and adequate examples can now be picked up for

around £150. (2001 prices) The V8 engine creates no special problems

providing you don't want ultimate power, while the suspension should be

reasonably simple to sort, perhaps using Escort technology at the rear -

there is no suggestion that the standard system can be made to work using

'legal' parts, so a Rover 3500 rally car will have no pretensions as an

international contender. All in all, it should be feasible to produce a

winning club car, with perhaps 250bhp and weighing no more than most Mk2

Escorts, for about £5,000 (2001 prices)- which is about half the price of

an equivalent more modern car.

|